Prof. ir.

Wim van den Bergh Architect

Prof. ir.

Wim van den Bergh Architect

1981/02a

Selected Realisations

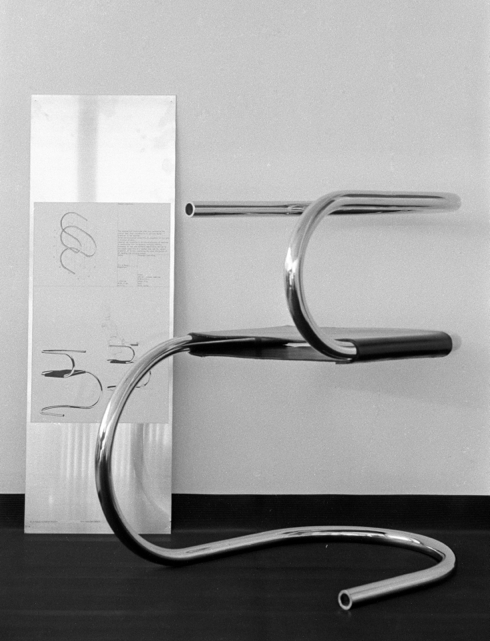

“Mono-tube Chair”

Publications: 1983/01, 1988/05, 1991/06

Exhibitions:

Realisations

Design intentions

The idea for the asymmetrical ‘Mono-tube Chair’ was born from a re-evaluation of the tubular-steel chair’s evolution towards the cantilevering principal of the famous 'Freischwinger’, in the late nineteen-twenties. The design represents a critical re-thinking of the concept of the tubular steel chair according to its initial design intentions then.

Being:

•serial and economical production, by simplicity of form and a minimum of parts to be assembled

•the use of material according to its intrinsic nature, like the resiliency of steel tube, but now in combination with the enormous torsion stability of its closed section.

•expression of form and aesthetic appreciation, derived by the simple clear line of a single bend tube.

Prototype

Competition entry for:

8e Biënnale Interieur 82

1982, Kortrijk, B

First Production 1984

Normal version (10)

Nickel plated steel tube / Leather seat

First Production 1984

Shorter version (10)

Nickel plated steel tube / Cane seat

First Production 1984

Stainless steel version (1)

Glass-blasted Stainless steel / Leather seat

Graphic panel

Competition entry for:

Progressive Architecture’s First “International Conceptual Furniture Competition”

1981, Stamford, Connecticut, USA

Mono-tube chair

The asymmetric mono-tube chair is the result of a design process that seeks to go beyond the one-dimensional translation of a function into an utilitarian product, its a design process that also associates itself with the mythical traces in our memory and the obsessions produced in the design process through form and material. In this case, the selected theme is that of the tubular steel chair, which is driven to its extreme consequences, thus to do both, build an 'ironic' argument as well as developing a serious alternative.

The idea of the tubular steel chair was based on Michael Thonet's mid-nineteenth century industrial concept of mass producing inexpensive bentwood furniture. Which he achieved by means of a simple and efficient form determined by the material, its natural properties and a process of production that tried to minimize the number of different parts and operational stages of production. In the mid nineteen-twenties this industrial concept of bent-wood furniture was converted to bent-steel-tube furniture by among others Mart Stam, Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe. In their minds and hands this industrial concept of the economy of means and resources, combined with the application of a new material and the fun of inventing an ingenious construction, was transformed into the 'console' principle of the 'Freischwinger'. A prototype that since then has been reproduced in countless variations, but without any real innovation or evolution because the ultimate consequences of the aforementioned principles were never put up for discussion.

The tubular steel chair presented here tries to grab those material properties and production methods and drive them to the extreme. In its "simple" form it not only uses the strength and elasticity of the steel-tube, but also the potential of the enormous torsional strength that a tube possesses (by means of its closed cross-section). Further an old and naive obsession or paradox is investigated within the theme of the tubular steel chair, namely the stability of the 'stoel' (chair in Dutch), since stability and 'stoel' (like in the English stool) in etymology have the same Indo-Germanic root 'sta', to stand, with derivatives meaning "place or thing which is standing". And further how this standing and stability of the 'stoel'/chair is reconciled with its comfort and as such the material it is designed in. In terms of design it becomes the obsession to use both the stability and the flexibility of a steel-tube and to imagine and deform this straight tube with the grace and elegance of one smooth flowing line into a chair, a 'machine' that in its apparent lability possesses a stable stiffness and pleasant suspension to to bluff gravity. In this case the tubular steel chair isn't a 'sitting-machine' in the sense of Posener, but more a 'machine' in the meaning of Deleuze and Guattari, a 'machine' consisting of five parts - a floor surface, a curved tube, a seat, a person and gravity - and only in the interplay of all five elements sitting is being produced.